Part 1: Girl meets Ooze

Some games that you played as a kid come with a whole raft of memories attached. Weeks spent reading previews and eagerly anticipating a title. Day after day of sitting rapt in front of a television screen chipping away at difficult hurdles with siblings or friends, or planning strategies for a new play of a beloved title on the last day of school ahead of the summer holidays. Those games are part of the very fabric of your childhood; foundational pieces of media that shaped you in just the same way as beloved cartoons or books from your early years.

Other games from childhood can be equally special or memorable for... very different reasons. And for me, The Ooze was one of those games. In about 1996, we had just moved to a new town, and as was the custom for my brother and I (and, I suspect, most 90s kids who weren't rich enough to afford regular new video games), we quickly registered with the local video store to systematically rent any game we could find there that looked interesting. It wasn't a big store really. Most ones in Scotland weren't, outside of the then fairly rare Blockbusters. And before long we had gone through all the store's proper bangers like Shining in the Darkness and Wonder Boy in Monster World, as well as a handful of unknown oddities like the gorgeous but otherwise not especially noteworthy Flink.

Then there was The Ooze. My brother and I often joked about it when we saw the cover. Featuring a big goofy slime monster wreaking havoc on a handful of dudes in red hazmats, he thought it was hilarious for some reason, and me... Well, I was a bit younger, and I think I low key thought it was pretty scary. But hey, he laughed, so I laughed too. “The Ooze!” we would giggle each time we visited. “Let's rent The Ooze!”

And eventually, when there was nothing else to rent, we did.

I don't think we got very far with the game at all. Maybe to the second world, at a stretch, but I'm not convinced we even beat the first boss. The game is really, really hard, as this review will go on to discuss, so I can't imagine we saw much of it. But what we saw was, for me, more than enough. From the moment the game began and we heard a sinister heartbeat over the Sega logo, I was terrified. I really, really didn't like stories of nature being corrupted as a kid. Of body horror and grotesque mutation, or science being used to do horrible things to living creatures. And that's basically The Ooze's whole jam, so it was... decidedly not a good time for little me.

I didn't want to look bad in front of my brother by that age, and I don't think I ever told him I found the game so scary. I think I kind of played it off as thinking it was pretty bad, and given that even he couldn't get anywhere with it, I think we were both happy to leave it at that and go back to playing Magic: The Gathering for the day. The Ooze went back to the shop the next day, and outside of continuing to see that slimy, slimy man with his big red eyes staring at me from the shelf every time we went, that was that.

But that was decidedly not that for me. I was really upset by the game, in truth. By the grungy, ominous melodies, the intro sequence where the protagonist is forcibly injected with green goop to sinister music, the unsettling title screen, the protagonist's pained death animation, and just the sheer oppressive ugliness and cruelness of the game and its world. I didn't like any of it at all, and thought about it anxiously a lot for the whole summer afterwards.

It didn't get to the point of waking up after nightmares of big slimy monsters, necessarily, nor was it even bad enough that I felt I needed to tell anyone. But I think as you get older, you eventually hit a point where very little in fictional media scares you anymore, and by the time I hit my teens, I had become a huge horror buff, and can't recall any piece of fictional media after the age of about twelve that properly upset me for any length of time. And I would have been about ten when we rented The Ooze, I guess. So looking back on it, it was probably one of the final pieces of media that upset me in that deep, genuinely traumatic way that childhood media encountered before you're ready so often can.

I guess that's why it stuck in my head so much despite probably not playing it for more than an hour. After old favourites like Shining Force, Sonic, and Phantasy Star, I suppose it would've been one of the very first Mega Drive games I revisited in my teens, when we first got access to the internet. Amusingly, I remember starting it up with a degree of proper trepidation because of the unpleasant memories, and I suppose some part of me probably sought out the game because she wanted to put that to rest. And hey, to be fair it did! The game still had that spooky, grimy atmosphere to it, but as a teen I realised how goofy and B movie-ish it all was, and why my brother had probably laughed at it back in the day.

It was still punishing, though. Like good god. A lot of childhood games that you revisit with a bit more experience, better resource management, and more honed fine motor skills wind up being a pushover, but The Ooze still kicked my ass as a teen. Again, I made very little progress, and again, the game was put aside after just an hour or two. But once again, I found it lingered in my memory. Not out of fear this time, but simply a kind of fascination. I realised as a teen with more experience of the medium how weird the game actually was, and between that and my strange little history with it, it was one I thought back to countless times over the following years, revisiting the soundtrack and parts of the game once Youtube popped up in the mid-2000s, and always carrying the vague sense that for a whole raft of reasons, it was one I needed to go back to and finish someday.

Just a few days ago, I finally did. So these are my overly lengthy thoughts on The Ooze, which slimed its way into my nightmares at the age of ten, oozed back into the picture for me in my teens, and continued to fascinate me until I finally dragged my own decaying, gooey old body across the finish line in the year of our lord 2024.

Part 2: The primordial Ooze

So what is the game all about, anyway? Who was that big slimy man on the cover, and how did he come into being? The Ooze actually carries a surprisingly fine pedigree, being developed by Sega Technical Institute, the once famous creative laboratory of veteran Mark Cerny that is perhaps most renowned for its work on Comix Zone and the Sonic sequels, and boasting Stieg Hedlund as its lead designer, who was later a key figure in the development of landmark Blizzard titles like Diablo and Starcraft.

Despite the presence of these now big names, though, the game failed to make much of a splash at the time, even compared to other late releases like STI's Comix Zone. Today it is remembered by few, as far as I can tell, and fetches high prices in the second hand market, particularly in Japan where it is one of the rarer games on the console and was saddled with one of the most bizarre, unfitting pieces of box art this side of Phalanx. Japanese Wikipedia suggests that the cover designers just did whatever they wanted because “only the really hardcore fans were going to buy the game anyway”. I have no idea of the veracity of this fact, but it is extremely funny regardless. The game's Japanese Wiki article also directly cites Mega Drive Mini producer Hiroyuki Miyazaki, who stated during a celebratory event for the launch of the console that the game only shipped 800 copies in the country, and had the lowest print run of any Mega Drive game released in Japan, which combined with the box art, makes it pretty wild that it released at all.

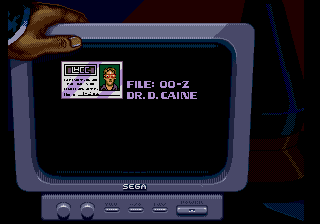

The game's story drops the player into the shoes (shooze?) of Dr. Daniel Caine, a bespectacled scientist oddly reminiscent of Milo Thatch from Disney's Atlantis, who boasts a so-bad-it's-good pun of a name that only became apparent to me as an adult when I saw it written as “D. Caine” on a monitor in the game's opening. An employee of the sinister Corporation (no, it's literally called The Corporation), Dr. Caine begins to suspect that his employer is involved in some certified bad shit. Staying late after work, he breaks into confidential company files and discovers the existence of Operation Omega, The Corporation's plan to engineer a devastating plague and turn enormous profits by supplying the cure to world governments.

Alas, The Director (you know, The Director of The Corporation?) gets wind of his intrusion, and injects the hapless protagonist with a ghastly green goo intended to kill him. The disintegrating remains of Daniel are flushed down a toilet, and The Corporation's files declare him terminated.

But the good doctor doesn't die. Whether by a miracle of individual biology or simply sheer dumb luck, the serum intended to erase him instead preserves a green, gooey version of his head, a single hand, and the remnants of his humanity. And upon awakening, the protagonist discovers with a mixture of horror and a heady sense of newfound power that the rest of his body that was disintegrated into green goop is still completely within his control, and that he can both manipulate his new form and use it to dissolve and absorb other living things, increasing his own mass. With these strange powers, Dr. Caine sets out on a slimy quest for revenge against The Corporation and a way to restore his human form.

Part 3: Not very Oozer friendly

There are two major things the internet will tell you about The Ooze. One is that it is a fascinating, unique game concept that isn't quite like anything else on the Mega Drive or really many other games even now. This is true – I have continued to think about the game on and off for literal decades after first renting it all those years ago, after all. The other thing people will tell you, though, is that it is brutally, viciously difficult, staggeringly frustrating at points, and borderline unfair, to the point where most people seem to abandon it during the third world or even earlier. And this, sadly, is also true – I've already mentioned my lack of progress with the game as a kid and as a teen, but even as an adult, learning and finishing the game with the good ending without the benefit of save states was a daunting task that took me over eighteen hours split over many, many lengthy attempts.

Naturally The Ooze is not the first game with a difficulty curve that slips towards the unreasonable. Difficult games always toe a delicate line between being satisfyingly challenging and feeling outright frustrating and mean-spirited. And though I'm not sure there's any one factor that determines which side of that line a given game falls on, I personally think a big part of it comes down to effective framing of a game's difficulty, which is, along with the game's lack of passwords or continues, where I think The Ooze really struggles.

When I encounter a game where I'm not convinced the steep difficulty totally works, I always find myself thinking back to some of the most memorable, satisfyingly difficult games I've played – examples like Madeline's battle with a fierce, hostile mountain and her own inner demons in Celeste, or Arthur's foolhardy quest through a wickedly cruel world in Ghouls n' Ghosts. Each of these games approaches its difficulty in quite a distinct way, I think, but both are quite effective.

Celeste constantly reassures the player that in the face of impossible odds, they can triumph if they just don't give up, and take a moment to breathe between each seemingly insurmountable obstacle. It stresses that even as the game kills you over and over, it really wants you to advance, and to ultimately succeed. The developer is in some way on the player's side, and the difficulty is almost a shared enemy to be overcome.

Ghouls n' Ghosts, by comparison, presents its difficulty as a core part of its identity and something of a cruel joke on Arthur, a dubiously qualified protagonist so far out of his depth that a single hit will reduce him to his underwear. The player is invited to laugh at the absurdly unfair odds the aspiring hero is presented with, and teased into testing themselves against a quest that sometimes feels like it borders on the impossible. The game makes it clear from the very earliest point that it is going to be grade A bullshit all the way through, and that it's all in good fun. And I think that's a big part of why the game and its equally cruel series have remained well liked despite being just about as wilfully nasty as games come.

Both of these approaches are valid, and I feel both are successful in mitigating some of their respective games' frustration. Of course they both still made me rage at times – it never feels very good to lose repeatedly at a given challenge in a game. But both of these games, as well as many others I've played that do difficulty “well”, as it were, are ones that quickly establish solid expectations of what kind of difficulty will be presented to the player, and frame that difficulty in a way that feels thematically consistent and compelling, motivating the player in some way or another to push themselves that little bit further through each new challenge.

The Ooze is, unfortunately, one of those games that has a bit of trouble when it comes to this, and I think it's at the core of why the game feels so needlessly cruel to play, and why it seems to have frustrated so many who tried. I read quite a few articles and reviews of the game over the course of learning the game, and a complaint I saw quite a few times was that the game doesn't make good on its promise of allowing the player to be an unstoppable monstrosity, rampaging through levels and tossing enemies aside effortlessly. That Dr. Caine is far too fragile, and the gameplay overly slow and meticulous. While I'm not sure myself that said promise is one that the game makes explicitly, it's certainly hard not to see it as the implicit suggestion from the developer when, for example, the player reads the game prologue in the manual, which talks of Caine awakening to a “strange power, like the force of a tidal wave” post-transformation, or looks at the game's cover that depicts Caine as a hulking, monstrous creature towering fearlessly in front of his pitiful human enemies.

None of this is completely misleading, mind, as Caine is certainly a powerful character. His gooey “punch” can curve around corners to hit enemies from well outside of their attack radius, and traverse huge distances when the player has enough ooze in their body mass. And his lack of a traditional health bar allows the player to tank enormous amounts of damage and emerge victorious so long as their head remains intact – I was often able to squeeze through absolutely hectic situations that would have killed most standard action game protagonists thanks to Caine's small hitbox when he's on the verge of death, and then recover by regaining enough ooze before his body collapsed. You're also able to one or two shot a good chunk of the normal enemies in the game with both Caine's punch and his toxic spit, and his punch can be spammed incredibly fast at close range on certain boss targets, so he's able to deal out hefty damage if you can find the right opening.

These are all big advantages that would be borderline game-breaking in many titles, and in a one on one battle Caine nearly always has the upper hand. So the game does, in a manner of speaking, make good on its presentation of the character as an unstoppable force of vengeance. Still, despite all these advantages, the titular ooze is an incredibly fragile protagonist. Any serious hit to the head will lead to the instant loss of a life, no matter how large his mass is, making even replays of simple, familiar levels nerve-racking due to the genuine threat posed by every single enemy and hazard. Caine is also at his most powerful only with a significant body mass, but moving around at this size both makes him a bigger target, and leads to plenty of situations where hazards are so tightly packed that the player is literally unable to safely traverse an area without dropping a huge chunk of their mass in one go.

This combined with the meagre amount of lives allotted to the player and the total absence of continues means that death is never very far away for the protagonist despite all of his powers, and the player has to be constantly alert to a degree that is almost exhausting at times. So I do think it's fair to say that there's a slightly uncomfortable conflict between the power fantasy that the game sets up for the player, albeit implicitly, and the very precarious scenario that actually plays out once the game begins.

I'm not sure it really had to be like that, either. Dr. Caine is essentially the broken vestiges of a man held together by nothing but rage and a strange quirk of chemistry. He was also, as far as the game tells us, not a skilled combatant prior to his transformation. His enemy, by comparison, is virtually omnipotent – an unspeakably evil corporation so large and omnipresent that it is simply known as The Corporation, which appears to have such significant resources and influence that it's able to throw an almost endless supply of soldiers and monstrosities at Caine, and dabble in everything from appalling environmental pollution to murder, ethically dubious genetic engineering, and the creation of devastating plagues with no significant opposition from anything other than the protagonist's green fist.

All this is to say that the odds are, even with Caine's newfound powers, not exactly in his favour. He is a slimy, disgusting underdog; a few sparse fragments of a basically dead man bound by chance to a puddle of hazardous goo, which crawls from the toxic dump where it was discarded through shit-filled sewage pipes and toilet bowls towards what is almost certain doom, but may also just offer the faintest hope of revenge and salvation.

Looking at the oppressive, unyieldingly tense levels on offer here, hearing Caine's constant guttural cries of pain as his body is torn apart and reformed time and time again, and seeing the agonised writhing of his little pixellated face each time the game cuts dramatically to black and his head melts away to nothing to the sound of Howard Drossin's dramatic, painful death cue (a scene almost as upsetting and scarring to me as a kid as the game's title screen, given how jarringly it can be sprung on the player at any point), I feel that whatever Sega Technical Institute's intentions were and whatever the manual and promotional artwork conveys, that's ultimately the story the game tells for the majority of its runtime – one of a slow, gruelling struggle in the face of pain and despair. And I can't help but feel like the punishing difficulty would have been palatable to a much wider audience if they had just leaned into this angle a little more explicitly.

Had they, say, emphasised the weight of the obstacles in Caine's way and the fragility of his tenuous grip on life a little more, and invited players to celebrate the glory of his unlikely successes against the odds with something more than “you win!” written in gooey red text and an awkward series of images depicting him returning to a (surprisingly buff!) human form, I think the struggle would feel more compelling to the player, and the game's hurdles more narratively justified and less cruel for the sake of it. As is, though, it often feels like the game simply hates both its protagonist and the player controlling him. Like it is setting out to simply ensure that the player suffers for no reason, and angrily resisting progress at every turn. The game is The Corporation, and The Corporation wants you dead (and if the unsettling bad ending image is to be believed, turned into a particularly ghastly lava lamp).

That is, of course, itself a valid approach to difficulty, and one that will speak to a certain kind of player (as someone shamelessly stubborn, I know I'm somewhat inclined to put maximum effort towards proving I can finish a game that tells me to fuck off at every available opportunity). But it's a much narrower niche than a game that invites the player to understand the reasons for its difficulty and treats them as an active participant in the game instead of someone to be tied to a chair and slowly tortured.

Part 4: Slimy yet satisfying

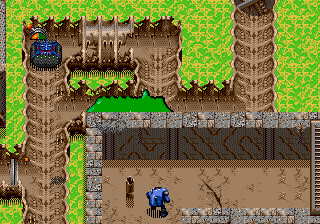

It's a shame, too, because beneath the absolutely punishing difficulty and the frustration is a pretty fascinating experience. The Ooze is presented as a top down action-adventure with a visual style that's not a million miles away from something like The Chaos Engine by The Bitmap Brothers. The pixel art can be a bit inconsistent at points, with the final set of levels feeling particularly uninspired, and certain elements like the Genetics Lab boss having a weirdly unfinished, amateurish look to them that is really jarring. But by and large I think it's quite well done, and contributes to some really atmospheric and suitably unpleasant environments.

The Ooze himself is a cool creation in motion as well, with some really fun little animation flourishes to his face, and neat and then quite sophisticated tricks pulled with sprite coordination to really make him feel like a cohesive body of liquid that expands and contracts with the environment around him. He's also an interesting attempt at avoiding onscreen HUD elements while still making important information legible to the player – Caine's size conveys at a glance how close he is to death from dissolution, while his head is (in theory, at least – the hit box is a bit finicky) always a single shot to kill regardless of size.

Idling for a few moments will even have him hold up a hand with a number of slimy fingers equal to the amount of DNA strands (optional collectibles necessary for the good ending) that you've picked up in a level. And while this isn't mentioned in the manual and I'd question whether something that took me fifteen hours to notice is intuitive game design, it's certainly a cool and novel solution to keeping the screen clear of numbers, albeit one that fails to convey other information like the player's remaining stock of lives. Regardless, while the game looks unimpressive at first glance for a game from 1995, and in many ways it is given that it released the same year as titles like Alien Soldier, I think it has a fairly solid visual identity that grows on you as it goes on.

The music by Howard Drossin is also fantastic as far as I'm concerned. A grimy, grungy rock soundtrack with great riffs and melodies that achieves a rich, full sound despite its use of the much maligned GEMS driver, it's perhaps the single biggest driver of the game's formidable atmosphere. The Toxic Dump, title, and intro songs stuck with me for years after my short time with the game as a kid, intertwined with my vague, unsettling memories of the game. And finally arriving at the Plague Factory as an adult after struggling through the game's most oppressive obstacles was made that much more triumphant by a dramatic tune that really drives home that the player is in the home stretch. Heck, even the song for the Waste Plant, which goes in for some of the more flatulent sounds that GEMS games could be notorious for, totally works for me in a game about such a gloopy, awkward protagonist, and slithering around the level to it feels just right. It's just great stuff all around, and very much a grimier cousin to Drossin's equally cool, distinctively 90s work on Comix Zone.

Part 5: The Ooze seeks his own level

It's absolutely the gameplay, though, where the game is at its most interesting and unique. As previously touched upon, Caine moves around levels in a top down format, his body expanding and contracting in response to his motion and the surrounding area. Being a liquid, the protagonist is vulnerable to drains and similar gaps in the scenery, with any parts of his body that make contact sloughing away at a rapid rate, demanding that the player remain vigilant of their surroundings at all times.

Many of the game's levels are rather large, with some even featuring multiple exits leading to distinctly different paths through the following level. And the levels themselves tend to be quite inventive in the challenges they pose to the player's ability to manipulate Caine's unique form. A handful of narrow gaps through obstacles require you to approach in a state of motion so that Caine's tail end is stretched further behind him and not expanded outwards where it will be sheared off or collapse into pits. Other challenges require you to slingshot yourself between grippable poles; the mechanics of this can be a little fiddly to get a handle on initially, but it's satisfying once you do, as Caine stretches out and pulls his whole body thin, weaving his body through obstacles in the way. Power grids that will sear away Caine's mass in certain spots must be manipulated safely from distance, or require the player to pick a safe spot on the grid and stretch out a slimy arm to hit a switch in a more dangerous spot, retracting just as the grid bursts into life. Meanwhile, automatic doors will shear Caine's body in half as they close – the player often needs to squeeze themselves into small gaps between two alternating doors, or put themselves back together again each time they're sliced apart. And then there are the many, many laser turrets...

It's mostly quality stuff, honestly, and while the slightly imprecise nature of the controls and the extremely punishing nature of many of the challenges makes it less fun than it might be otherwise, there's a proper inventiveness to the level design that shows that for all the developers' struggles with game balance, they put genuine thought into how their unique protagonist ought to interact with the world around him. It's also interesting that while the game initially seems like it's going to be about keeping your form as large as possible and avoiding damage entirely, this simply isn't practical in reality. As previously mentioned, most areas beyond a certain point are impossible to traverse without losing at least some of Caine's body, and while this absolutely increases the difficulty, it also creates an interesting dynamic where the challenge is more in understanding the advantages and disadvantages of different sizes of form, and being able to get the best out of all of them in different scenarios.

Additionally, though the game's difficulty does border on unfair too often as previously noted, and was undoubtedly the wrong choice in my mind, it certainly lends a sense of tension and menace to every moment when married to Drossin's soundtrack, and can be really effective in the sections where it doesn't swerve into outright frustration. I never felt properly safe in The Ooze, even in levels I knew well, and there's something that can be said, I think, for a game that continues to inspire that sense of trepidation after so many hours, even if it sometimes resorts to needlessly punishing means to do so.

Unfortunately much of my praise in these areas drops away when it comes to the three levels of the Plague Factory, the final area, which is largely composed of barren corridors populated by enemies. On one hand, it's a dramatic deescalation of difficulty from the staggeringly difficult Power Grid levels that precede it, and arguably as easy as the game ever gets outside of the first few levels. But on the other, it simply doesn't feel entirely finished. The Plague Factory is also interestingly the only area in the manual that does not feature a screenshot, opting instead for concept art. And while part of that could be a desire to hide the final challenge from the player, with the rough state of the levels, I can't help but wonder if maybe they were running behind time crafting the game's final challenges. A couple of sadly unused bangers from Drossin in the sound test seem to add further weight to that theory. Regardless, on the whole I still think the game's level design is surprisingly strong provided you can deal with its penchant for punishing, borderline unfair traps, and I found a whole lot to like in that area.

Part 6: Spit, punch, it's all in the mind

Where the game is a bit less successful is in its combat. As I've mentioned, Caine has two modes of attack. The first and more common ability is to stretch his body out towards enemies, propelled by his single remaining fist. This slimy “punch” can be bent in various directions during its movement, allowing for interesting (and often compulsory) strategies like bending it into difficult to reach areas where dangerous enemies or gun turrets lurk, or keeping enemies that will melt the doctor at close quarters at a very safe distance.

The other more damaging option is to spit part of Caine's body at a target. This is only outright obligatory for one section, the second world boss, but is a useful tool in your arsenal, especially late game when you run into a lot of robots that explode on death, and are actually dragged closer to Caine by the retraction of his arm when he punches them, forcing you to quickly move out of the way to avoid getting blown apart. It does, however, come at a cost - since you're literally spitting your body at targets, this will cause Caine to slowly shrink away, creating an interesting risk / reward mechanic with your most powerful weapon, and restricting its use entirely when Caine is at his smallest size.

Unfortunately both of these options, despite their interesting qualities, have some issues. Guiding Caine's punch has a pretty decent learning curve, and while you will get better at it eventually, it can be enormously frustrating to begin with. As it's directly connected to your body, it can also create difficulties in certain environments - it will immediately retract at the cost of health if it hits something damaging and can, as previously noted, pull dangerous targets closer to you late game. The spit attack also has its downsides. You're not able to spit when directly under attack, perhaps to stop you from spitting away so much health that you die. But this creates problems with a few enemies, particularly the little scorpion guys that latch onto you in the Genetics Lab and kill you in seconds. The punch is too slow and needs to be precisely aimed at their small hitbox, while the spit can't be used once they're latched on. My strategy became to approach their eggs close enough that they hatch, then immediately pull back and throw a punch to catch them as they spawned, but it's awfully precise, and the cost is pretty grave if you miss. This is admittedly the worst example I can think of of this sort of situation, but it is reflective of a pattern where the game sometimes places you in situations where neither of your two weapons really feel suited to the situation at hand.

Part 7: That's a DN-nay from me

The game is also very fond of hidden paths, which are usually disguised in very ordinary looking tiles with no visual clues offered to the player of their existence. To be fair, once you've googled one or two of them you'll start to get an idea for where the game likes to hide them, and they don't become overly difficult to find, but it's still a questionable design decision that didn't sit entirely right with me. Many of these hidden paths also lead to bonus stages where Caine is tasked with murdering a certain number of mutated lab rabbits (nobody said this game was high brow) in a certain amount of seconds, which can be an opportunity to regain lost ooze, and also offers a DNA helix should he be successful in defeating the rabbits and leaving the stage within the time limit.

These helixes form the game's optional content - there are fifty scattered around the game, with five in each non-boss level, and one of those five in each level coming from the bonus stages. The problem with this doesn't come from the scavenger hunt itself, which is quite fun and adds another layer of challenge to the game, but with the total lack of reward for pursuing this frankly quite daunting goal. Caine's buff green human form will emerge from a puddle of ooze in a series of still images in the ending, with his progression towards a full form changing depending on how many helixes you found. But literally nothing changes beyond that.

For a game that cites Caine regaining his humanity as one of his key objectives, and sets up quite a fun wee scenario in its opening scene and manual prologue, the lack of care given to the resolution of this central plot point feels careless and disappointing, and further contributes to the sense that the game's finale was unfinished. It's understandable that such a late Mega Drive release had to be rushed to market before it lost any minor relevance it might have had, but I feel that even adding some text crawls between levels and to the ending would have done so much to tie the whole experience together, and would have been a quick and easy way to add a more satisfying narrative resolution to the true ending.

To add insult to injury, the bonus stages that contain ten of the game's helixes also allow only a single try each. Fail even one, and you're effectively locked out of the already underwhelming good ending for that whole run. I did find a hacky workaround where letting the rabbits kill you before time runs out allows you to retry a given bonus stage from scratch, effectively allowing you to trade a life for another go if it looks like you're going to fail. But it really shouldn't be a case of things coming to that, and the whole helix quest feels ill conceived from top to bottom in the end. A shame, given that the incentive of restoring the protagonist to some semblance of humanity is quite a compelling hook, and a potentially very fun conclusion to the game's shlocky B-movie story.

Part 8: Concloozion

Should you play The Ooze? I don't know. That the game presents an unreasonable, unjustified, and largely unrewarded challenge is, as far as I'm concerned, beyond question. But whether said challenge is actually any fun moment to moment will probably depend on the player. Me, I really enjoyed slowly puzzling out the game, especially given my history with it and the unpleasant experience I had with it as a kid, and I think it's an interesting and worthwhile experience that stands out in the 16-bit landscape despite its warts. But I'd be lying if I said it didn't make me unspeakably angry at times.

For every inventive, cool piece of level design, there's an almost unbearably tight gap to weave through with invincible gun turrets, or an exploding robot hidden beneath a roof (I began reflexively firing Caine's arm into every one of these on principle after too many surprise deaths). Despite the game's enticing atmosphere and killer tunes, its story is completely discarded after the opening, and the conclusion feels hollow and unfinished, with no real reward for players who bother to collect the DNA strands and restore Caine's humanity. Challenges that are tense and exciting on first run can become tiresome on the many replays necessary to learn the levels. Combat provides some really cool options with the controllable arm and risk / reward of spitting away Caine's body, but can be imprecise against certain smaller enemies. And while the game's oppressive challenge will certainly speak to some players (it did to me!), I feel it's likely to alienate far more, and don't feel like it's contextualised well enough within the game to not simply feel like a cheap way of extending the game's lifespan in the rental market.

The choice to eschew passwords was also a big own goal for me that makes it harder to recommend. The game is lengthy, with my final successful run clocking in at over three hours. And while I had plenty of lives to spare by the end and it's very beatable on a single go with a lot of practice, the need to maintain a high level of concentration for its relatively long runtime is exhausting, and the slow, meticulous nature of the game doesn't lend itself well to repeated replays, with the first two worlds, especially, becoming tiresome to replay constantly due to their comparative lack of danger once learned. I'd be reluctant to recommend that anyone undertake so much repetition to learn a game with so many issues. There's a point where not allowing players to continue where they left off starts to function less as a legitimate extension of the game's challenge, and more as a way to waste a player's time, and I think this one crosses that point and then some. Passwords weren't needed here because the game is hard (though it is), but because the game's format would simply function better with them. And it's a bit of a shame that the developers didn't realise that.

But did I enjoy The Ooze, after all these thousands of words? I think I really did, you know. From getting closure on a weird, silly trauma from my childhood to exploring the game's genuinely unique and cool aspects while jamming to Drossin's bops, and from the cool, interesting (and often memorably rage-inducing) level design to the gradual satisfaction of seeing every ridiculous hurdle the game threw at me be overcome, I really did have a whole lot of fun with this one, even as I saw a few runs evaporate late game due to a string of misfortunes, or swore like a sailor as lives were snuffed out in early levels by a stray laser or two. The game is kinda bullshit, but you know what? It's my bullshit, now more than ever. And I'd do the whole ridiculous thing again. My head says it's a 6 or a 7/10 at best. But I look at that slimy, slimy man on the cover now, and my heart screams "YES!" in that weird little voice sample of Dr. Caine's when you collect a DNA helix. So fuck it, The Ooze game of the year all years. All time greatest game in the niche genre of ooze games. Highly recommended.

PLATFORM: Sega Mega Drive / Genesis

CLEAR TIME: 18:09:33 (total of all attempts - final run time 3:19:14)

REGION: NTSC-U

PLAYED ON: Modded PAL Mega Drive

barleybap

barleybap